The New Wave of Indian Type

Studying the open source, collaborative work of Indian typographers, as a model for global font design

As mobile access grows and more people around the world start using the internet—a billion people are expected to come online over the next few years in emerging markets alone—it’s also necessary to elevate the quality and range of digital typefaces available in different writing systems. This challenge is especially striking in India, a country that recognizes 23 official languages, but counted almost 1600 (including dialects) in their last census. Some of these languages and their scripts have descended from ancient Brahmi, others are based in Arabic, while the ongoing use of English, a language that's reach and influence has grown considerably since India's independence from Britain in 1947, means that Latin letters are also a common sight.

The Mumbai-based type designer Girish Dalvi has a gift for conveying the sheer scale of this typographic challenge. A professor of design at the Indian Institute of Technology and a co-founder of the Ek Type collective, Dalvi describes the immensity of Indian culture and language with a quote from the Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges, “India is larger than the world.” Dalvi allows a beat to pass before adding that Borges did, in fact, have a good rationale for this saying. “India is an extremely diverse country,” says Dalvi. “The language and script change every five hundred miles, and so does Indian design.”

Keeping pace with the subcontinent’s linguistic diversity is challenging enough in print, but the relatively small number of digital fonts available for Indic languages reveals a striking disparity. Even the most widely used Indian script, Devanagari, has far fewer typographic options compared to the superabundance of Latin fonts. Some scripts like Bengali, Tamil, Urdu, and Tibetan have even fewer fonts available. But the balance is beginning to shift as a cohort of Indian type designers develop new digital fonts, and the movement is still growing in part because many of these designers release their designs with open source licenses. The code is then readily available for others to experiment and develop their own contributions, improving the quality and variety of typography across India’s many writing systems.

Addressing regional needs

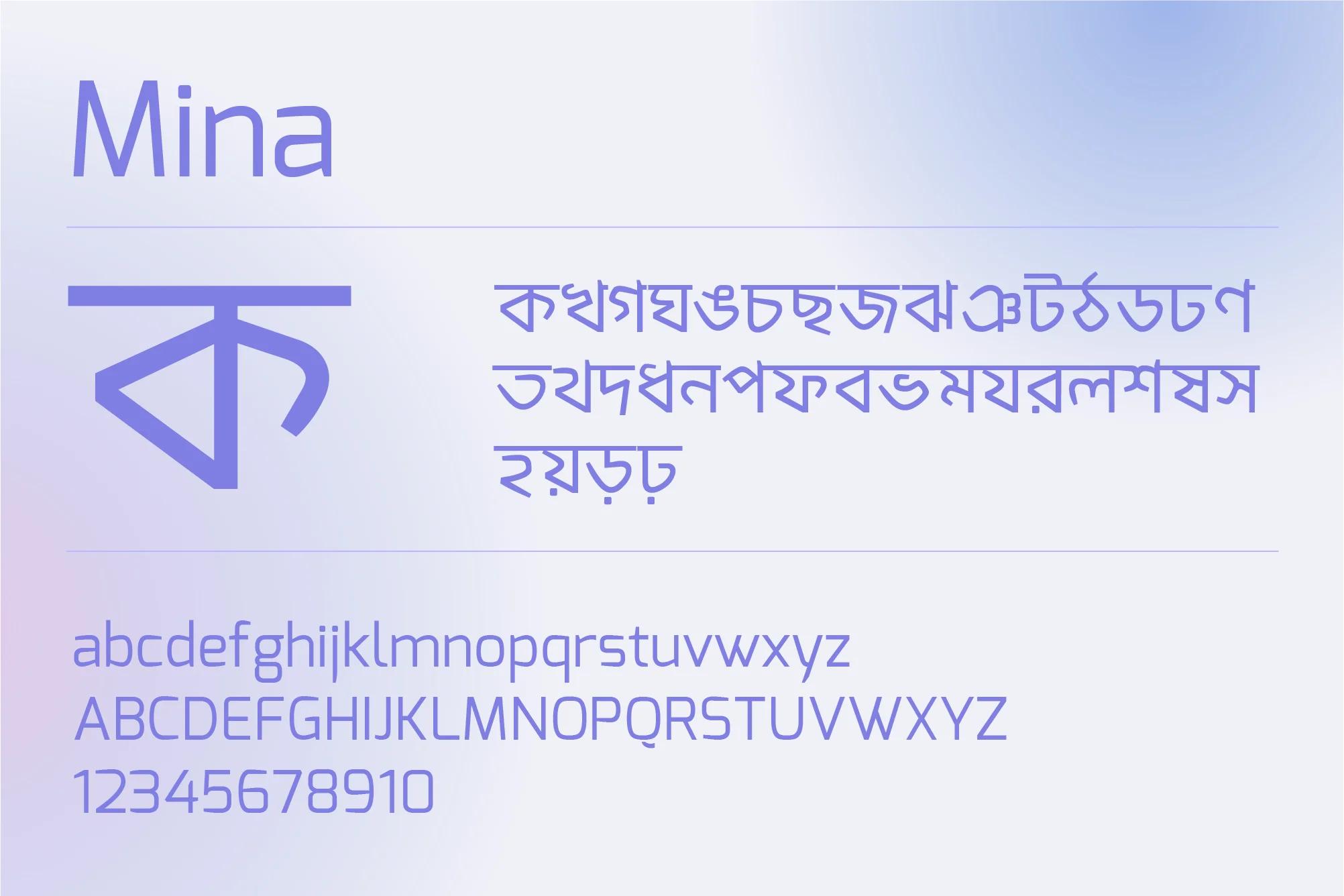

Focusing on the challenges particular to Indian typography and solving for them has led to the creation of digital fonts that typically pair the Latin script with a single Indic script. Mina, a font created by the New Delhi-based designer Suman Bhandary, has addressed a need for one of India’s larger linguistic populations—Bengali speakers.

“There is an extensive need for diversification through regional languages across India,” says Bhandary, who used the open source font Exo as a template to design Mina when he recognized how few fonts were available for the substantial Bengali speaking population. “Bangla being the seventh most spoken language, the user base is huge compared to the awareness and the availability of well-designed web fonts.”

New fonts may also increase the variety and aesthetic complexity of digital typography in different scripts by drawing from calligraphic models. The Sri Lankan type designer Tharique Azeez created Pavanam and Kavivanar after noticing “typographic monotony” in Tamil books and websites despite the expressiveness found in the handwritten script. “Everything looked the same,” says Azeez. “I wanted to give a richer and more authentic look to Tamil typography.”

Azeez is particularly interested in typographic experiments and uses this drive to expand the typographic landscape in South Asia. “When working with Pavanam, I explored different ways to incorporate subtle stylistic terminals since the fluctuating descenders and ascenders of Tamil glyphs give the designer room to play with spacing and decorative details,” he says. “I keep exploring different styles for Tamil typography on a daily basis.”

Mukta: Designing a single font solution

The only problem with designing for one script at a time is that Indian websites and publications often need to present multiple scripts together. But since different scripts have their own distinct features and eccentricities, it’s unrealistic to expect two Indic typefaces in different scripts to pair well by chance alone.

With Mukta, Dalvi and his collaborators at the Ek Type collective approach India’s diverse typographic needs at a larger scale—the full scale, in fact. The mission behind Mukta is to create a common visual grammar that works across all of India’s writing systems. The challenge is to create a harmonious overall appearance between these scripts while also preserving the distinctive characteristics of each one. So far, Mukta covers five of the most widely used scripts in India—Devanagari, Gujarati, Gurumukhi, Tamil, and Latin. Those five scripts support seven or eight of India’s most widely used languages, together spoken by hundreds of millions of people across the Indian subcontinent.

Mukta is drawn in a contemporary humanist style that makes it useful in many design roles. Each of its five scripts were fine-tuned to hang together visually so they can be used side by side.

The Latin variant of Mukta may look familiar. It’s a neutral, workhorse, humanist sans serif with a tall x-height, neatly modulated strokes, and a wide range of weights from extra-light to extra-bold (but no italics). So far, so good. But problems arise when you switch to a script like Devanagari, whose characters have more strokes and greater overall complexity than Latin. You can make an “H” bolder without worrying too much about squeezing its form and straining legibility, but many Indic letters lose their distinct features and blur together if special attention isn’t paid to their overall shapes as they become heavier on the page.

Mukta’s designers had to decide which letters in each script were amenable to different adjustments, such as expanding and creating space between strokes. Dalvi says they found this balance in Mukta by building “a common visual grammar,” that matches the axis (tilt), modulation (variation in the width of strokes), and apertures (enclosed, interior spaces) of letters to create a consistent appearance while preserving the dominant features of each script.

The range and versatility of Mukta is already making an impact. Most of India’s major newspapers now use the font for their online editions, because it covers such a broad swath of their readership. The Hindi newspaper Dainik Jagran and the Marathi newspaper Lokmat use the Devanagari variant of Mukta.

Using open source design to promote typographic diversity

Designing a font from scratch can be very time-consuming, but sharing access to the source code can help with the heavy lifting and ease the way for other designers. Imagine placing the lines and points that form the general outline of each letter. Much of the work is repetitive, but instead of starting from scratch, existing fonts with an open code base can serve as raw materials for other type designers to cut to the chase and produce original work.

This has been one of the motivations behind Ek Type offering their pan-Indian type projects Mukta and Baloo as open source projects. The collective released the full source code for Mukta under a free and open source license so that its huge range of high-quality glyphs can serve as raw materials for students to learn type design, and for other type designers to do original work in different Indic scripts. Anyone can download the source code for an open source font like Mukta from Github and ‘fork’ it into their own offshoot of the design. Just as Bhandary’s Mina was based on Exo, the code for one font can aid in the development of something entirely new.

The Baloo project supports ten writing systems used in India. Three are shown above: Devanagari, Latin, and Tamil.

Experimenting with software is how the members of the Ek Type collective got started themselves. “We weren’t taught type design,” says Dalvi. “We learned by programming things, hacking things, breaking things.” Even the name Mukta—meaning free, open, or liberated—nods to their commitment to open design principles.

Mukta provides a starting point for some of the most widely used Indic scripts, but any open source font (including the entire Google Fonts catalog) can be forked and reimagined as something new. In order to create greater typographic equity, there are many other scripts like Arabic, Ge’ez, and Myanmar in which contemporary typographic options are often slim relative to their substantial number of readers.

The enormous linguistic diversity of the Indian subcontinent is in many ways a microcosm of global disparities in type design. The gap between the wealth of Latin fonts and the relative scarcity for other writing systems is only magnified when you consider how many are used by India’s distinct ethnic communities. India might not be “larger than the world,” but its typographic dilemmas are essentially the same ones that designers confront any time they’re not using Latin-like alphabets. The solutions discovered and improved upon by Indian designers could very well apply the world over.