Contrary to Popular Belief

A personal tale of managing your career by molding your character

I can’t count the number of times I’ve been called a lazy Mexican. It never stops hurting, but it stings when it comes from another Mexican, especially your father.

My father is a religious man who believes that hard work is essential for worldly and spiritual success. When I was a kid, he tried to drive out my ‘laziness’ by making me do all sorts of busy work—polishing his already super shiny shoes, mopping the already spotless floors, rearranging my already organized closets. The outcome of these tasks wasn’t important as long as I was always working, always moving, always doing. The devil can’t catch what doesn’t stand still.

Sundays were no exception. This was the Lord’s day of rest, not little Hector’s. One time after church, I asked my father if I could see my friends. He told me to clean the garage first. I protested that it wasn’t even dirty, but he shouted, “Not dirty isn’t the same as clean.”

I can laugh about this now, but the accumulation of so many incidents in my formative years instilled in me the core belief that I’m lazy. It didn’t help that when I moved to the U.S., I was confronted with the stereotype that Mexicans are lazy. I interpreted every piece of feedback I received—like “this mock is imprecise” or “that idea isn’t thought through”—as an implicit criticism of my laziness. I worked constantly, nearly destroying my health and career in the process.

I’m not sharing this because I find it therapeutic to publicize my struggles, but because I’m convinced I’m not the only one who has them. No matter how successful or confident you are, you’re probably fighting a few toxic core beliefs of your own. If you’re unaware of them, these beliefs might be directing your life and career, like some invisible broken compass. While you can’t change the events that led to your core beliefs, you can change your core beliefs and, in turn, your life and career.

From broken compass to breakdown

While beliefs and core beliefs both shape how you see yourself, the latter are more insidious—they’re like a tiny invisible compass deep inside your character that directs your movement through life. You unconsciously sustain them by focusing on evidence that reinforces their existence, ignoring that which contradicts it. My compass was broken. The symptoms I was experiencing were as long and embarrassing as a disclaimer on a pharmaceutical product. Perhaps, though, the biggest symptom was being overworked.

At the time, a senior vice president asked my team to deliver concepts for a top-priority project. What an opportunity! Sadly, my team was at capacity, and nobody could put in the extra hours. So I decided to model hard work and took it on myself. I stayed up late for weeks and neglected everything else—sleep, diet, exercise, my family. I was on my way to Karoshi, the Japanese term for “death by overwork.” In the end, I produced an enormous amount of beautiful mocks that, although duly acknowledged, was all for naught.

And yet, deep down, I knew that would happen. I knew that I was doing busy work for my own perverse gratification—but I couldn’t stop myself. Something inside of me impelled me to keep moving.

I wasn’t completely oblivious; I knew I wasn’t at my best. I was so desperate for help that I was grasping for whatever I could find. I took courses on productivity strategies, got executive coaching, read self-help articles. While they gave me momentary relief, the positive effects were fleeting because I was treating the symptoms, not the root cause.

A trip to the emergency room is what helped me to identify that underlying condition. After I turned in all those beautiful—and ultimately pointless—mocks, the adrenalin wore off, and the physical and emotional pain hit me like a brick. Suddenly, I couldn’t speak. I couldn’t move my hands. I couldn’t even focus my eyes. My wife rushed me to the hospital and the doctor diagnosed me with burnout. She gave me a shot of steroids, prescribed some medication for the pain, and sent me home to “take it easy for a few weeks.”

Take it easy for a few weeks? That’s the worst-case scenario for somebody who always needs to be moving. All I could do was lay on my couch in a state of physical and emotional paralysis. I remember the notifications coming from my phone—concerned colleagues, family, and friends checking-in—and I had neither the desire to speak with anyone, nor the willpower to turn off the buzzing phone. Worst of all, my daughter had been diagnosed with an illness and needed me. But I couldn’t be there for her. I couldn’t even be there for myself.

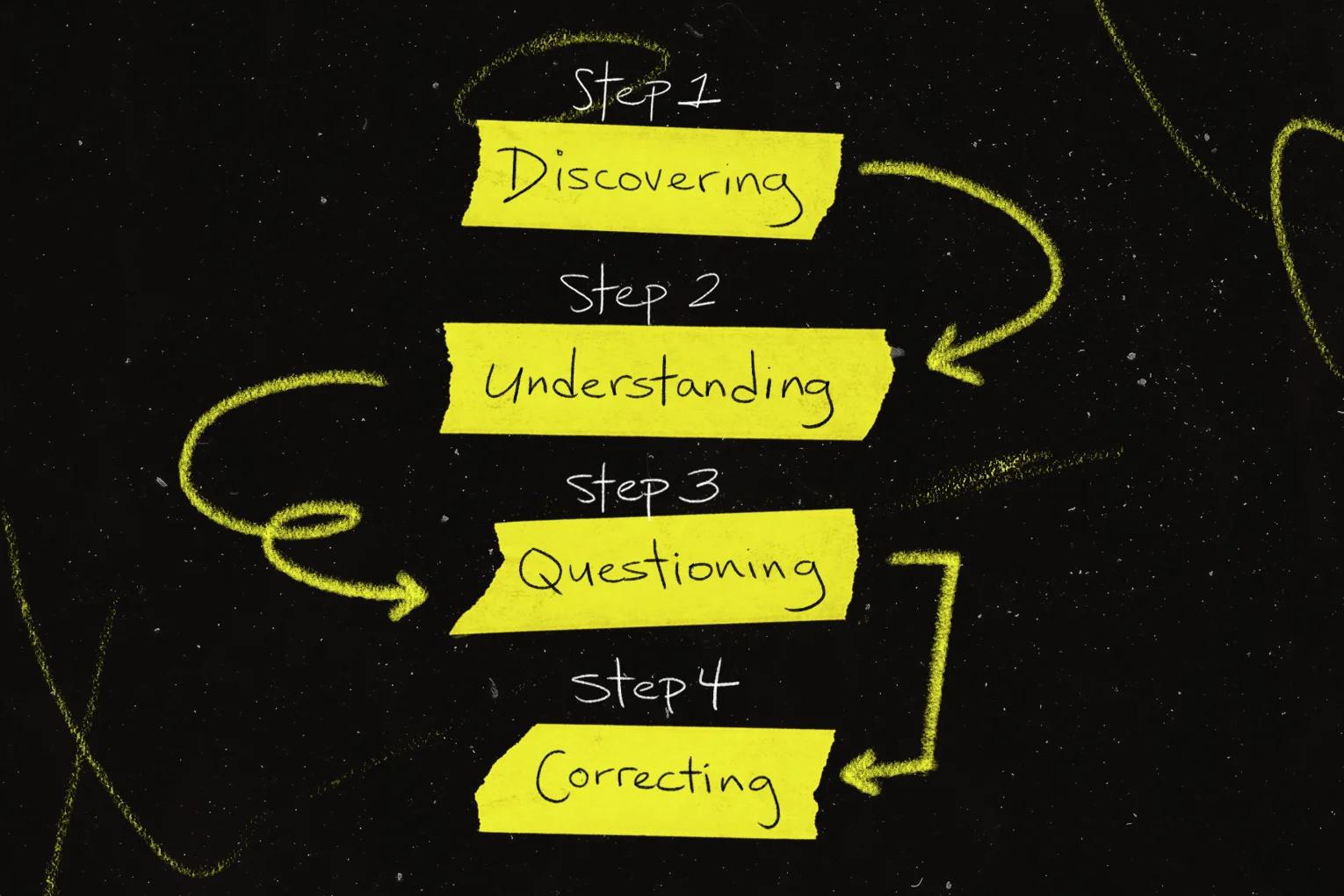

My process to discover, understand, question, and correct my core beliefs

After a few weeks of wallowing in my uselessness, I was determined to make sense of my breakdown and build myself back up again. It became clear that a set of deeply-seated toxic core beliefs was behind everything wrong with how I was leading my life. So, I began a process of identifying my toxic core beliefs, questioning their validity, and reframing them into something positive.

Step 1: Discovering my core beliefs

In those weeks after the onset of my burnout, I said and did a lot of things that made me feel bad about myself. One memorable episode happened when my daughter asked me to read to her while I was lying on the couch. I told her to brush her teeth first. She didn’t want to and we started to yell at each other. Then my wife ran over and yelled at me, “Why do you always make her do little things and add conditions—just read the freaking book!”

My wife was right—why couldn’t I just read the book? I felt guilty for reasons I couldn’t articulate. I decided in that moment to write down exactly what happened and dissect my motivations. I did this by asking, like a child, an endless series of questions:

I yelled at my daughter today. Why? Because I don’t like when she doesn’t obey me. Why? Because I’m her father and I asked her to do something. Why? Because I don’t want her to think everything is free. Why? Because I never got anything for free in life. Why? Because my father forced me do stupid little chores. Why? Because he wanted me to be hard-working. Why? Because I’m often lazy. Why? I dunno...

Once I reached this point of no further regression, it became clear that I had run into something at the core of my character: I believed that I was lazy.

Step 2: Understanding my core beliefs

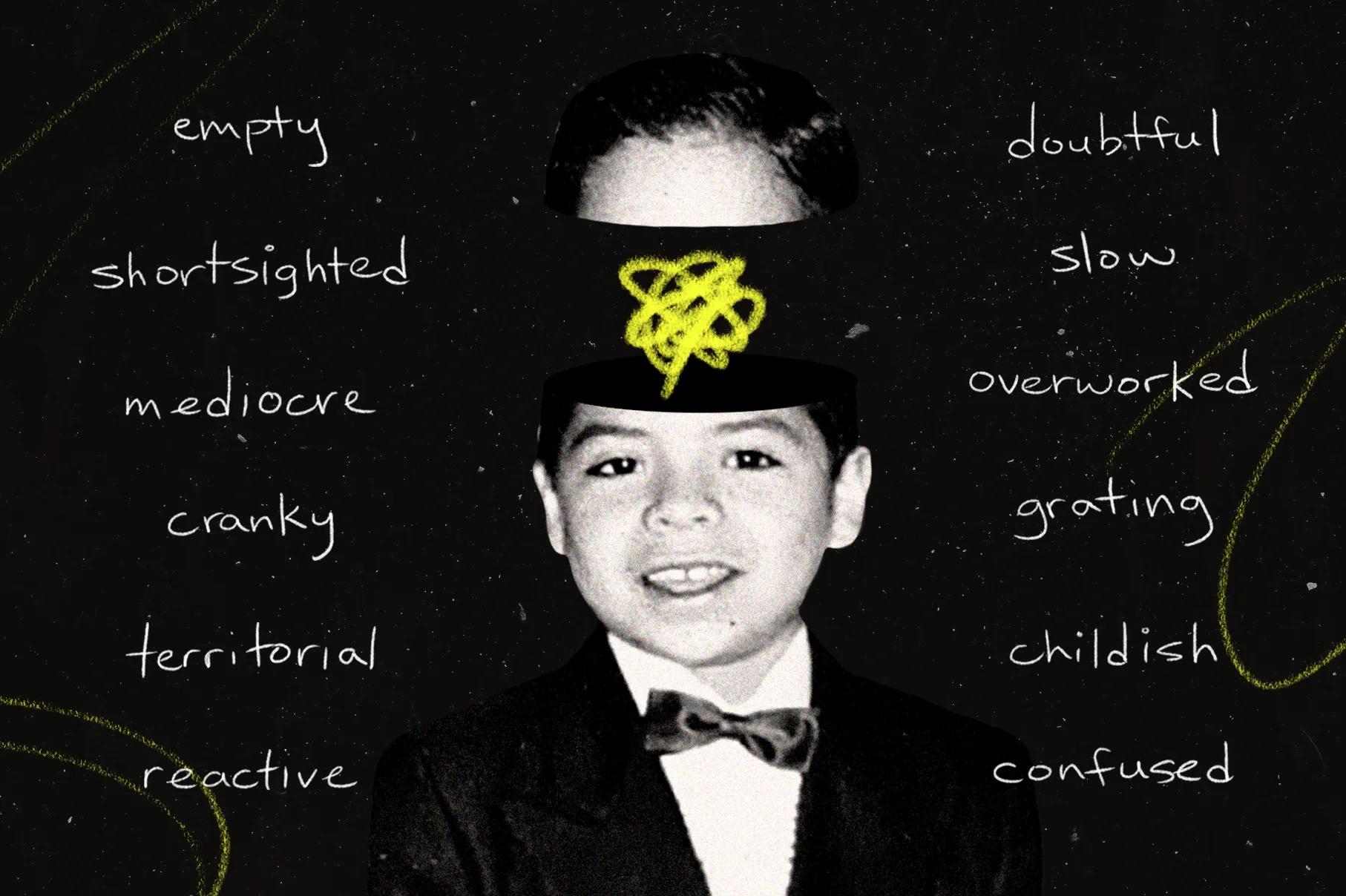

It didn’t stop at laziness either. In the coming days, I used this method to discover a whole series of toxic core beliefs that, like some splinter lodged deep down in my character, caused me pain whenever I rubbed against them:

I’m superficial.

I’m frivolous.

I’m odd.

I’m sinful.

I’m never good enough.

Formative events in my early life—like my father making me feel guilty for resting or schoolchildren making fun of me for wearing badass clothes—inculcated in me these negative beliefs. The more I considered their origins, the easier it became to discern how my negative behaviors were a consequence of fighting against these beliefs, like the body trying to push out a splinter. I could see how the core belief that ‘I’m lazy’ was driving me to work myself into the ground, staying up all night creating mocks for a futile project.

Step 3: Questioning my core beliefs

Something, though, felt wrong about some of my conclusions. At times, it felt like I was only focusing on the behaviors that reinforced the existence of these toxic core beliefs, not the ones that contradicted them. I could think of many occasions where I worked really hard because it genuinely felt good. For instance, when I hand-painted the party invitations for my grandparents’ 50th anniversary party, I did all that work not to show off (to whatever extent that’s possible, as I paint like a kindergartner), but because it made me feel good. A lazy person wouldn’t have done that. Such contradictions between what my core beliefs were and how I often didn’t fulfill them is what ultimately allowed me to change the narrative.

Step 4: Correcting my core beliefs

As a designer, I don’t think in bugs—I think in feature requests. Why not apply this same perspective to my personal life and transform my character defects into something that helps me? I did this by analyzing my negative core beliefs and extracting their hidden advantages:

I’m lazy → I’m deliberate about what I do

I’m superficial → I’m expressive

I’m frivolous → I like to socialize and connect

I’m odd → I’m unorthodox

I’m sinful → I enjoy things

I’m never good enough → Sometimes I’m great

These reframes essentially transformed toxins into remedies.

A very ~~lazy~~ deliberate Mexican

But you can’t switch around some words and expect poof—I’ve been cured of the belief that I’m lazy and am now deliberate here on out. Toxic core beliefs can’t be permanently cured, only continuously corrected. You need to keep these reframes in mind and deploy them as soon as you feel the symptoms.

I know what activates my toxic core beliefs and causes the negative symptoms. Big and complex problems, for instance, can easily trigger my don’t-be-lazy-reflex and cause me to jump head-on and work frantically when what I really need is purposefulness and clarity of mind. I have to constantly remind myself, “Hector, take it easy. You’re not lazy, you’re deliberate.”

I’m now very deliberate about where I choose to put my energy. Said in fancy economic terms: I appreciate the opportunity costs and comparative advantages involved in my ‘doing’ and ‘not doing’ certain things. I only take on projects that align with my skills, interests, and desired areas of development. This ensures that, when I am working, I’ll be at my best and most productive.

At the same time, I’ve also come to recognize how productive I can be at work when I’m, well, not working at all. Before March, I’d take long walks in the park outside my office and let my mind wander. Now that I’m confined to my home, I sit in my backyard and watch insects crawl up my apricot tree. I’ve discovered that these moments of idleness, these seemingly frivolous hours, are when I have my best ideas—which, in my line of work, is the chief metric of productivity. That’s why my work day is now full of times where I’m actively disengaged and ostensibly doing nothing. I’m fully aware that this fulfills the stereotype of ‘the lazy Mexican’ who needs to take frequent siestas, but I know my idleness makes me more productive.

Careful careering

Over the years, I’ve worked hard to get better at work. I’ve attended countless courses and conferences, taken on projects outside of my comfort zone, and read every management book I could find in airport bookstores. While these investments have all helped, my most significant and sustainable performance boost has undoubtedly come from recalibrating my core beliefs. It’s given me a sense of sovereignty that you can only attain once you’ve fully embraced who you are and who you aren’t, what you can and can’t do. This self-awareness has given me the confidence to turn down offers and opportunities that—because they don’t align with my skills, interests, and desired growth areas—would’ve ultimately made me unhappy.

Most people jump at every big opportunity and unwittingly head down a career path over which they have no control. If you want to be in control of your career, you need to first be in control of yourself. This starts with confronting and correcting the core beliefs that, lodged deep down in your character, are unconsciously guiding your actions and behaviors. So if you care about your career, start with your core beliefs.